I've been upfront with you—these little articles will include some math (or at least understanding some basic math concepts and relationships).

But don't panic or start thinking this is calculus-level stuff (although I'm sure some of you could handle it). It's basic arithmetic, and trust me, it can seriously change your life (or at least your perspective).

Math is the language of finance; we have to get into the numbers. We'll also dive into some real-life examples to make things clear. Why? Because understanding these ideas is a whole lot easier when you see them in action.

Let's start with our first elementary example —we will predict someone's net worth one year from now.

First, a couple of short definitions from Investopedia:

Asset: “A resource with economic value that an individual owns or controls with the expectation that it will provide a future benefit.”

Examples include home equity, real estate, cars, jewelry, stocks, bonds, and bank accounts.

Liability: “Something that is owed to another person, company, or government.”

Examples include home or car loans, taxes payable, credit obligations, parking tickets, etc.

With that, here's what we're working with:

Assets: $50,000 earning a guaranteed 5% per year – Liabilities: $0 ( good for them) (Note: I’ll discuss how assets like home equity fit in these calculations in another article, but that is not highly relevant to young adults just starting out.)

Net Worth: $50,000 (assets minus liabilities)

Annual Income: $50,000

Taxes: $4,000/year (est.)

Giving: $4,000/year

Living Expenses: $30,000/year

The Question: What will this household's net worth be in a year?

The Answer:

Let's break it down:

Starting Wealth (Savings): $50,000

+ Income: $50,000 = $100,000

– Taxes: $4,000/year (est.) = $96,000

– Giving: $4,000/year = $92,000

– Living Expenses: $30,000/year = $62,000

+ Interest Earned: $50,000 × 0.05 = $2,500 = $64,500

This household's net worth ("wealth") has increased by $14,500. $2,500 from interest and $12,000 from surplus income (after taxes and expenses) have added to the starting wealth of $50,000.

See? That wasn't so bad; it's really just adding and subtracting numbers. This example leads us to a simple formula, which I’m going to call our “Financial Life Equation,” or FLE:

Next Year's Wealth = Current wealth + Next year’s income – Next year’s taxes – Next year’s giving – Next year’s living expenses + Next year’s interest earned – Next year’s interest paid

We could express this symbolically like this:

Wt+1 = Wt + ∑It+1 –∑Tt+1–∑Gt+1–∑Et+1+ ∑IEt+1–∑IPt+1

Where:

FW = Future Wealth: A variable representing accumulated financial assets minus liabilities at the beginning of the period.

W = Current Wealth: Your current net worth based on total accumulated financial assets.

I = Income: Income earned during the period (e.g., salary, wages, tips).

T = Taxes: Taxes paid during the period, reducing net wealth.

G = Giving: Charitable donations made in cash, reducing net wealth (but increasing wealth laid up in heaven).

E = Living Expenses (a/k/a consumption): Consumption or expenditures also reduce wealth.

IE = Interest Earned: Interest earned on financial assets, contributing positively to wealth.

IP = Interest Paid: Interest expenses on liabilities, reducing wealth.

t = current time/date

t+1 = current time/date plus one year (t + n would be a variable, n number of years)

By the way, for you math majors out there who may be thinking, “hey, that equation isn’t 100% accurate,” here’s the academically correct version:

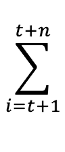

You math majors know what all the little letters mean. But for others, in the FLE, they are used to keep track of time; think of them as shortcuts for talking about money across many years:

i = the starting year (that’s usually now)

t = a specific year we're talking about (used to add stuff up year by year)

n = the number of future years you're planning ahead

So when you see this:

It just means: “Add up everything from next year through n years into the future.” That way, we’re not just thinking about money today; we’re calculating how all the variables affect your financial future.

I think you can see why I simplified it! My simplified version still conveys the idea of adding or subtracting the variables over just the following year (t + 1) or many years into the future (t + n). It's easier to follow and still helpful in illustrating the idea of financial cause and effect.

There's no magic here—it's just simple math. Most people think wealth is "what you save" after diligent budgeting. But saving is what's left after giving (which I’ve purposefully included in the equation), earning, spending, and paying taxes and interest.

(Some mathematical “magic” is part of the formula: compound interest. It’s the interest on the growth of our net worth year by year. We’ll get into that later on when we discuss investing.)

This highlights the importance of considering expenses, taxes, and interest paid, in addition to income and interest earned, when determining total net worth. The former are sometimes afterthoughts in the way that many people think about their finances.

This formula may be different from what you expected. Most people think of their future net worth as current wealth + savings:

Wt+1 = Wt + Savingst+1

This relationship is true when savings are defined as:

Savings = Income – Taxes – Giving – Expenses + Interest Earned – Interest Paid, or symbolically as:

Savingst+1 = It+1 – Tt+1– Gt+1– Et+1 + IEt+1– IPt+1

But I’d like you to think of the savings equation this way: Savings is not something you do; it’s simply what’s left over after you earn money, pay taxes, give, pay for living expenses, earn interest, and pay interest.

If you have nothing left, then you have no savings. In that sense, savings = margin. If you have no margin, you will have no savings. With no savings, no interest is earned (IE).

Some may say that margin = giving. I may have myself. And that’s also true to a point, but as you’ll see when we discuss giving in detail, I prefer to consider it an “off the top” expense, similar to taxes, not what’s left as margin. That is intentional, firstfruits giving.

Let's see how this works if we look out two years:

Starting Net Worth (after 1 year): $64,500

+ Income: $50,000 = $114,500

– Taxes: $4,000 = $110,500

– Giving: $4,000 = $106,500

– Living Expenses: $30,000 = $76,500

+ Interest Earned: $64,500 × 0.05 = $3,225 = $79,725

This household's new net worth at the end of the year has increased by approximately 20%. Things are moving in the right direction!

You can keep this going for as many years as you like, and the formula holds up.1 It boils down to this:

Future wealth = Starting wealth + Sum of all income – Sum of all taxes – Sum of all giving – Sum of all living expenses + Sum of interest earned – Sum of interest paid

The way that math textbooks express this in the formula is to use the Greek sigma symbol “∑” for “the sum of” and n for a "variable number of years” and t+n = current year (t) + (n) years. This is an “informal” (i.e., not technically correct) formula for expressing the equation:

Wt+n = Wt + ∑It+n –∑Tt+n–∑Gt+n–∑Et+n+ ∑IEt+n–∑IPt+n

Where:

Your starting wealth is (Wt)

The sum of your income over the next N years ∑It+n (where n= 1 to n years)

The sum of your taxes over the next N years ∑Tt+n (where n = 1 to n years)

The sum of your giving over the next N years ∑Gt+n (where n = 1 to n years)

The sum of your living expenses over the next N years ∑Et+n (where n = 1 to n years)

The sum of your interest earned over the next N years ∑IEt+n (where n = 1 to n years)

The sum of your interest paid over the next N years ∑IPt+n (where n = 1 to n years)

Even though you may never use it, this, my friends, is the most critical formula to understand your financial life.

This also brings us back to an earlier article: We begin with our “starting wealth,” but other things (“levers”) contribute to determining your future wealth and are aligned with the “earn, save, spend, owe, give” model I shared earlier.

This basic math construct shows us that if we wanted to, we could calculate our net worth 50 years from now (about my age). In that case, n=50. I’ll spare you the formula or a long description (it would use t+50) because nobody in their right mind would work it out using one (if the math and engineering majors want to, be my guest).

Plus, here’s the good news—some online tools are available to help you with this. Here are a few you might want to check out:

Automated Net Worth Tracking: Empower

Investing Integration: Betterment

Collaboration with Spouse or Financial Advisor: Monarch Money

Net Worth Calculator: Bankrate

Budget Integration: YNAB (You Need A Budget)

If I were to recommend one, it would be Empower—formerly Personal Capital. But many of you will also want to get some budgeting and investing tools. I’ll publish a separate article about tools (apps and online) down the road.

Subsequent articles will discuss the six areas I listed above and guide you on how to understand, manage, and optimize them.

I don't list giving because it's not a financial "lever" in the sense that the others are, but it is a potent force in driving overall financial success. I'll discuss why in the following article before discussing the six levers.

Some of what you will learn will be super actionable, while others will be more conceptual and involve understanding the big picture. Either way, you'll improve your financial acumen and long-term financial health.

For reflection: Even if you don’t like math, was it interesting that God created math in a way that could be used to describe real life, even the basic day-to-day things like personal finance? Instead of fearing math, consider embracing it as a gift from God to help you understand and apply biblical principles and practices of stewardship to your situation.

Verse: “Every good gift and every perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of lights.” (James 1:17, ESV)

You may notice that there is nothing about inflation in the formula, which, as we all know, affects future wealth. It is not included because it’s not one of the “levers” you can pull–you have little or no control over it. We will, however, discuss its effects and what you can do to mitigate them in future articles.