34—Lever #3: Spending (Part Three—Creating Margin)

Financial space for the unexpected, saving, and giving

Some people would like to save or give more, but can't. They might say that their expenses are too high or their jobs pay too little, making it challenging to find the extra money to save and give.

These can be legitimate problems—sometimes, income is the problem, and that's where they need to focus. Debt may also be a factor, so paying it down is a priority, which may leave little to give or save. But some would admit that their real problem is overspending and the lack of "margin" it creates.

I've mentioned the idea of "margin" several times in previous articles, but in this one, we'll examine it more closely and explain why it is such an important concept (and goal). When you hear the word "margin," your thoughts may gravitate toward time and how little we seem to have as we try to balance our work, home, and spiritual/church life. That kind of margin concerns the many demands these things make on our lives. However, while similar, margin in financial stewardship can be viewed from a couple of different perspectives.

First, it simply means having some ability to handle the unexpected. Did you know that about 4 in 10 Americans can’t handle a $400 emergency expense?1 One of the ways you do this is with an “emergency fund”—money you set aside for when “stuff happens.” (Christmas is not an emergency, by the way.)

Shoot for $1,000 to start, then increase it to 3 to 6 months of income as much as possible. That could help in the event of an unexpected job loss or a significant health issue. Consider a high-yield savings account or a government money market account to grow your savings. (You will have to open a brokerage account to hold a money market fund.)

Without that kind of margin, something unforeseen can wreck your finances. The "why" for this is apparent—margin provides some breathing room. You're better able to absorb life's punches.

The second type of margin, and the main focus of this discussion, is simply the difference between what you earn and spend. It’s like the margin on a printed page—the space between the printed area and the edge of the paper itself.

If you spend more than you earn, you have zero margin and may have a "negative margin" due to the need to borrow. If you spend less than you earn, you have margin, which allows you to save and give. Remember I > E? That's margin.

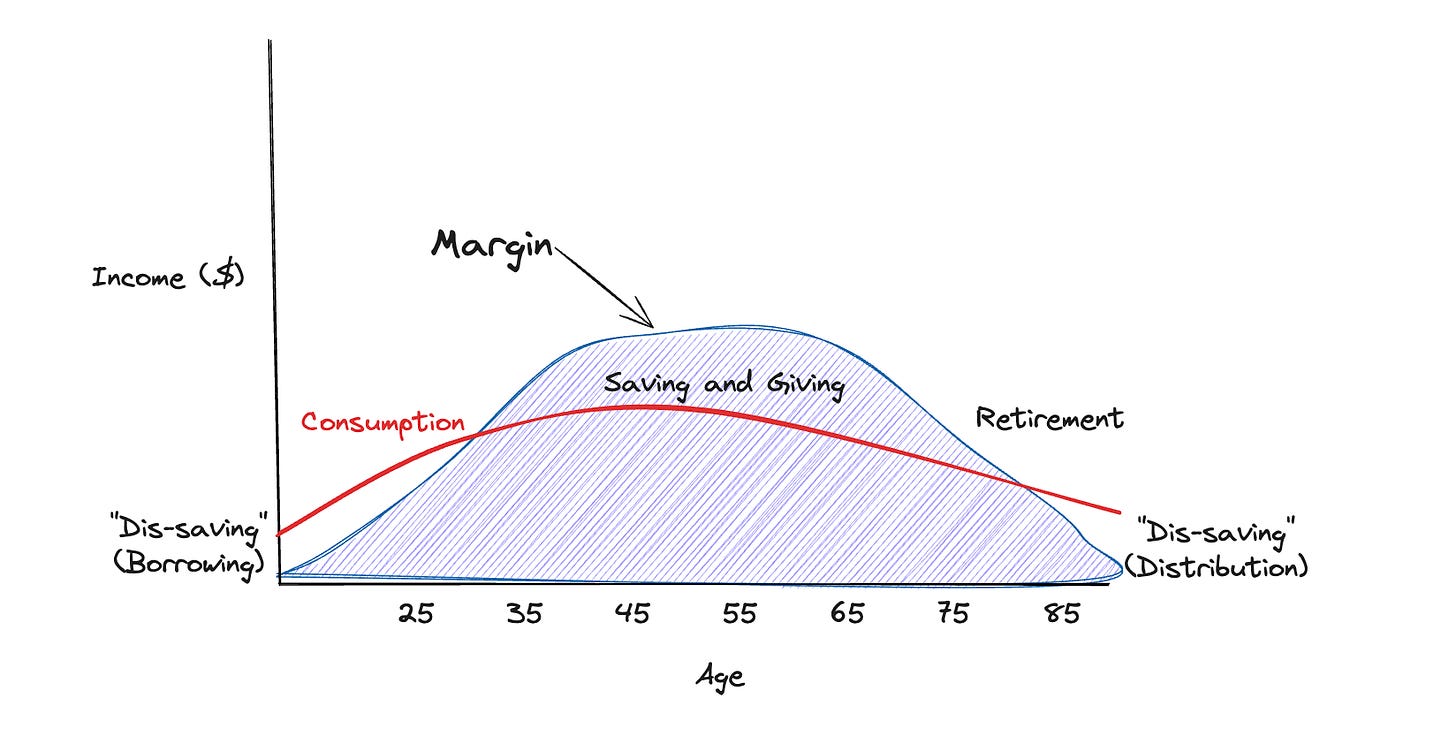

To further develop this concept and help you build financial margin, I would like to introduce the economic concept of "consumption smoothing." Flattening out consumption evenly over a lifetime can be a powerful tool in personal finance for creating margin. This chart illustrates the concept:

When you're starting out, you may have a negative net worth and margin (due to “dis-saving,” a/k/a borrowing). However, things usually trend positively once you leave school and start a full-time job or career.

I am referring to the earlier, lower-earning years, which I'm sure many of you have experienced, are experiencing, or will experience in the future. During this time, you want to keep your consumption (and, therefore, spending) as low as possible to minimize borrowing. Then, as your income and spending rise, you want to moderate it (smooth it out) so that you cease to be a borrower, pay off your debt, and start saving and giving.

Eventually, you will cease to be a low earner and become a middle to high-middle or even a high-income earner. During those years, by intentionally living below your means and resisting the temptation to increase spending in lockstep with income, you create a surplus that can be used for long-term financial goals, something you couldn't do in your lower-earning years.

A strong biblical principle aligns with the idea of consumption smoothing—the practice of wise, forward-looking stewardship. Proverbs 21:20 says, “Precious treasure and oil are in a wise man's dwelling, but a foolish man devours it” (ESV).

That verse highlights the wisdom of not consuming everything you have at the moment but instead setting some aside. The Bible consistently encourages diligence, restraint, and generosity, all of which require margin. Smoothing your consumption over time, rather than living at the limits of your income all the time, creates the space to give, save, and serve others, which reflects the heart of biblical stewardship.

Many young adults feel the urgency to start saving for the long term immediately. I get that, and a lot of popular financial advice leads you in that direction, and for a good reason: the incredible power of compound interest. I urge you to prioritize establishing an emergency fund (3 to 6 months of income) before aggressively saving and investing for long-term goals.

Most personal finance authors/gurus champion consistent, high savings rates throughout life. Many emphasize starting early, often citing the power of compound interest. I have beat that drum a few times myself. A common rule of thumb is saving 10-15% of income, sometimes more. But others (including many academics and economists) advocate for optimizing consumption (a/k/a "consumption smoothing") across one's lifetime.

They suggest that savings rates should fluctuate depending on life stages: low or negative savings in early life (perhaps out of necessity), higher savings in midlife (due to higher income), and negative savings (spending down assets) in retirement when you are no longer working for a living.

They also say that young individuals, especially those with borrowing constraints, may rationally choose to have little long-term savings or even debt and ramp up saving later on in life when they’re better able.

It's possible to start saving for retirement late and still accumulate enough, but it's not easy. My recommendation for those who get a late start is the same as the economists: saving more heavily in midlife when you're in your peak earning years and perhaps investing more aggressively can get you there, other things being equal.

Still, human nature being what it is, building a saving habit early is probably best, even if you’re setting aside a relatively low percentage. (I always recommend that young people invest enough to get their employer match in their 401(k) if one is on offer.)

And there’s the strong argument that starting young allows compound interest to do its ”miraculous work” over time. As Einstein reportedly said, "Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world."

Consumption smoothing is often less of a concern for high-income individuals because they have more savings and investments. Their income is typically more stable, and they are less likely to rely on credit. On the other hand, low-income individuals may struggle to save, and their reliance on credit increases, making them more vulnerable to income shocks.

Financial margin is equally critical to living free of anxiety and being poised to seize Kingdom opportunities. If we prioritize paying off burdensome debts (and avoiding accruing more) and squirreling away something every month for emergencies, we can begin to curb the anxiety that often comes with managing our finances.

What things “trip you up” in your pursuit of financial margin? Some factors—like mounting medical expenses or caring for the needs of those entrusted to our care—can be unavoidable during certain seasons of life. But we also battle the temptation to acquire things that bring us temporary pleasure or to attain a status imposed on us by cultural norms or societal expectations. And the barrage of enticements dangled over us each day by the Evil One can be relentless.

For reflection: How would you respond if your income were to increase by $50,000/year suddenly? Would you immediately think of all the things you could buy with that additional income, or would you take a more conservative approach, perhaps increasing your standard of living in a few areas but keeping some of your “new powder” dry as margin for other purposes? This highlights the head and heart challenges that accompany the discipline of creating and maintaining financial margin, a crucial aspect of wise stewardship.

Verse: “Five of them were foolish, and five were wise. For when the foolish took their lamps, they took no oil with them, but the wise took flasks of oil with their lamps.” (Matthew 25:2-4, ESV)