42–Lever #4: Interest Earned (Part Three–What Are You Saving For?)

Stewarding today’s dollars for tomorrow’s needs

Have you ever asked yourself, “What exactly am I saving for?” If you haven’t, you probably should.

The short answer may be “The future.” A longer one may be, “I’m saving for retirement,” or “to buy a home,” “to buy an Aussie-Labor-Spaniel-Doodle,” or “to get my teeth fixed.” Or, perhaps you’re thinking more short term: “I’m saving an emergency fund,” or “for a vacation trip next year.”

No matter what, it's pretty easy to see that there are two major categories of financial needs or wants you might save for: short/medium-term needs and long-term needs. You may be thinking, “What’s the big deal; a need is a need.” Yes, but the purpose of your savings does matter, especially in terms of 1) where you save (what type of account), 2) how you invest (to grow your savings), and 3) the tax implications of your decisions.

This seems elementary, and it is on one level. But the details behind it aren’t as simple as you might think. One reason is that you likely have numerous wants and needs, and you also have various options for saving and investing. The choices can make what should be a relatively simple decision seem overwhelmingly complex.

For example, let’s say you are looking for a high-interest savings account to park some cash for a few months, or a year or two. I found a recent Forbes article that said they evaluated “370 savings accounts from 157 banks and credit unions” to compile a list of recommended options. (Their top recommendation was the Synchrony High-Yield Savings account. It had a solid 4.00% annual percentage yield (APY), few fees, solid customer service, and access to ATMs.)

Just because Forbes looks at 370 accounts doesn’t mean there aren’t more—there are, but I don’t know how many; let’s say “lots.” And that includes brokerage accounts that can hold short-term money market and U.S. treasuries (a/k/a “T-Bills”—ultra short-term securities), among other investments. Almost every mutual fund company offers these accounts, regardless of whether they also offer a self-directed brokerage account.

In other words, you have lots of choices when it comes to savings, and we haven’t talked about investment vehicles yet. But before you decide on an institution, type of account, or investment that is right for you, think about what you’re saving for. Take a look at this diagram; it shows different categories of things you might save for, and differentiates them from the things you might invest in, although you can increase IE in both cases.

On the diagram, I’m using “Saving” to refer to money that is deposited in some relatively safe, interest-bearing account. “Investing” refers to money that is deposited mainly in a retirement account and used to purchase securities such as stocks, bonds, or mutual funds. (You can also hold securities in a non-retirement account; refer back to Article #30–Taxable Brokerage Accounts.)

I have included some suggested percentages, but they are just that, suggestions. You have a lot of flexibility in how you allocate your money in these areas, but, as we have discussed, a lot will depend on what you are spending.

Look at the boxes inside the “Savings” box. They are the primary things you might set aside money for to use in the short to medium term (less than 5 years). Initially, you need to save about 3 months of income in an emergency fund. Please make this a priority before you start saving for anything else, and bump it up as soon as you can (Dave Ramsey is right on with this one).

There are expenses and events that we can’t predict, which often lead to a reliance on credit cards to “make ends meet.” Therefore, these are the most common causes of unmanageable debt, which can sometimes ultimately lead to bankruptcy. An emergency fund helps you address them without using credit cards or dipping into long-term savings. Later, increase your emergency savings to six months of expenses to build a larger buffer if you can.

A major item replacement savings account is used for near-term, predictable needs, such as replacing worn-out items (appliances, computers, car tires, etc.). If you own a house, you also need to plan for expenses like a new roof, HVAC system, and water heater. A ”next car” fund is also in this category if you plan to pay cash for it, which, hopefully, you do.

Finally, you need a savings account for periodic bills and expenses. This one doesn’t require “extra” money. Instead, for each periodic bill or expense (those that don’t need to be paid every month, but do need to be paid sometime throughout the year), put one-twelfth of the annual amount on your monthly budget. Then, take the total monthly amount of all periodic bills or expenses and transfer that amount to yet another separate savings account, either physical or virtual. That way, when the bill comes due, the money will be available. Be sure to keep track of the virtual “sub account” balances in this fund.

Although I have called each of them an “account,” the money could be saved in a single account, with each of these being a “virtual” sub-account (think “mental accounting buckets”). (I would recommend you do that, but it is possible to hold multiple physical accounts and manage them accordingly.) If you use virtual accounts, you have to devise a way to keep track of them. So, let’s say, for discussion purposes, that you read the Forbes article, but you were wondering if you have other options. You do!

Regardless of your financial situation, for short-term savings, you want to keep your money safe and in an account that can be easily accessed for emergency needs and special purchases, such as a car, vacation, home furnishings, or Christmas gifts. Here’s a list of the major options:

Interest Checking Accounts offer very low interest, but sometimes more with higher balances. Plus, they are usually FDIC insured. (Of course, these can also be used for regular checking accounts for bill payments, etc.)

Savings Accounts are traditional savings accounts that typically pay very low interest, but are also FDIC-insured.

Certificates of Deposit (CDs) are deposit accounts that provide a fixed rate of return for a specific period. The longer the period (up to 5 years), the more interest is earned. CDs offer better returns than interest checking or savings accounts without risking what you have worked hard to save. CDs usually require a $500.00 minimum and are insured up to certain limits.

Money Market Accounts (MMAs) pay variable interest compounded daily and credited monthly. There is usually no monthly service fee when you maintain a certain minimum balance. You are typically able to write a limited number of checks each month, and you can also set up automatic transfers from your checking account each month or on payday.

Next are long-term savings, a/k/a “investing.” This is the other red box towards the top of the diagram above. We will discuss these next in the investing articles to follow, as this is an area where there are even more options (and therefore more “overwhelmingness”). Suffice it to say that the purpose of long-term investing is to meet future needs, especially for income in retirement (i.e, when you are no longer able to work for a living, or want to work for little or no pay, or do not wish to work at all).

The diagram shows a couple of tax-deferred retirement accounts, but as I mentioned earlier, you can hold long-term investments in taxable brokerage accounts. There are also other long-term investments such as real estate, some insurance products, precious metals, art, and cryptocurrency. However, most people will use an employer plan (i.e., 401(k) or 403(b)), an IRA, or both.

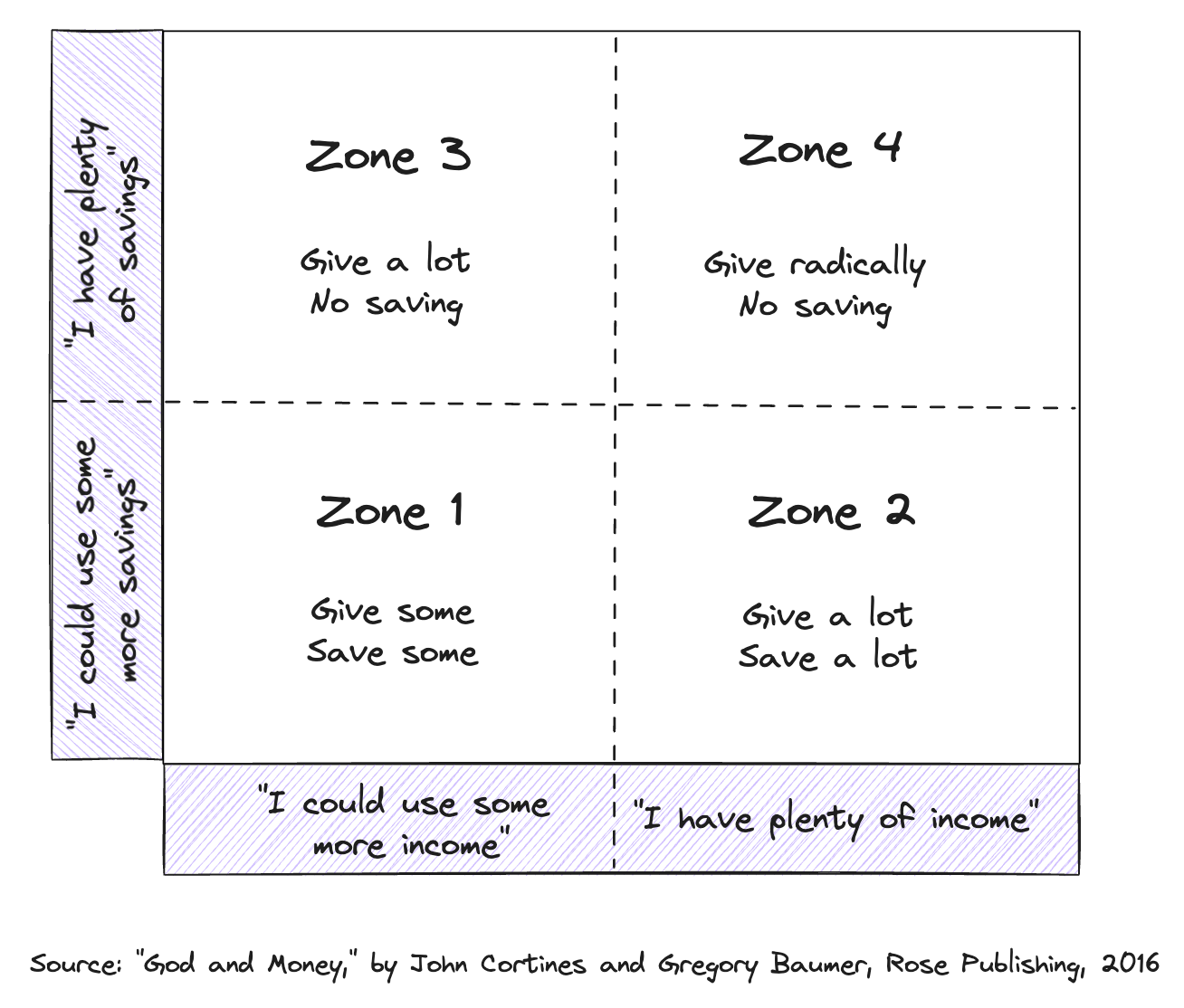

“How much is enough?” and “What should I do when I have ‘enough’ or ‘more than enough’”? These are excellent questions that you should strive to answer. They mainly pertain to long-term investing for retirement. Take a look at what’s called the “Servants’ Money Map”:

Most of your savings will be done in Zones 1 and 2 – the “I could use some more savings”… also called the “accumulation phase”; typically, between age 25 and 55 or later. Your goal is to reach Zone 3 or possibly Zone 4, where your saving goals are met and your giving can take off. This implies that you put a cap on your savings, and once you reach it, you free up more of your resources for generous giving. This recommendation is fully developed in the book titled God and Money: How We Discovered True Riches at Harvard Business School, which I highly recommend (and from which I obtained the above diagram). I hope they don’t mind.

I didn’t set a cap, but I did always try to give more than what I saved. If I were saving 15%, then I would give more than that. In a way, my “cap” was established automatically as I could only save so much if I were giving more. I’m not going to discuss your retirement savings “cap,” as most of you are decades away from making that decision. But please tuck it away in your memory banks somewhere so that you can recall it when the time comes.

Now that you understand the difference between short-term savings and long-term investing, you’re ready to learn more about the latter.

For reflection: If you’re already saving, have you ever stopped to consider not just how much you’re saving, but why you’re saving in the first place? Knowing the “what for” behind your savings can make it more purposeful and enjoyable. It also makes it an intentional act of stewardship rather than something you “just do” because someone said you should. Whether you’re saving for an emergency, a car, a house, or future retirement income, how you allocate your resources reveals what’s important to you. If you divert all of your margin to saving and investing, you are de-prioritizing giving.

Verse: “Precious treasure and oil are in a wise man's dwelling, but a foolish man devours it” (Proverbs 21:20, ESV).

Resources:

Search for High Yield Savings Accounts: https://www.bankrate.com/banking/savings/best-high-yield-interests-savings-accounts/

Book: God and Money: How We Discovered True Riches at Harvard Business School, by John Cortines and Gregory Baumer, 2016