28—Lever #2: Taxes (Part Six—The Traditional Versus Roth Decision)

To Roth or not to Roth, that is the question

In the previous article, we discussed the different types of retirement accounts. You will recall that Traditional 401(k)s and IRAs are currently untaxed but will be taxed upon withdrawal, while Roth 401(k)s and IRAs are taxed now and will not be taxed upon withdrawal.

I also gave you some basic guidelines on when it makes the most sense to use one account or the other (or both) based on current versus future marginal tax rates. In this article, we continue our Roth vs. Traditional (i.e., our tax-exempt vs. tax-deferred) discussion, and I’ll show you some more in-depth calculations that could help you better understand and decide.

I'm sorry. I wish it were more straightforward, but no thanks to the IRS, it just isn’t. If you want that, assume that future tax rates—both average and marginal–will be higher, perhaps much more so than today, and go with a Roth. But if you’re unsure, I’ll also explain why comparing your marginal rate today with your estimated average (effective) tax rate in retirement might be better.

Our basic working principle remains the same: The optimal answer, mathematically speaking, depends on your tax rate today and your future tax rate in retirement. However, this presents challenges today as it is impossible to know the tax rates 20, 30, or 40 years from now; we must make some assumptions.

If you read most of the popular literature, you will be told that the best way to decide between a Traditional and Roth 401(k) is to compare your tax rate today to your tax rate in retirement. That’s accurate to a point, but the most reliable comparison should probably be your marginal tax rate today versus your average tax rate in retirement.

Using the average tax rate in retirement makes more sense because not all of your withdrawals are taxed at your marginal rate. For example, if you are over 65 and married, filing jointly and withdrawing $60,000 annually, the first $34,700 (the standard deduction for 2025) is tax-free. The next $23,850 is taxed at 10%, and the remaining $2,950 is taxed at 12%. Here’s the tax calculation:

That’s an average federal tax rate of 4.3% based on income of $60,000. If you have a flat rate state tax of 5%, your average tax rate will be 9.6% even though your marginal rate is 12% federal plus 5% state, or 17%.

That shows why the average tax rate in retirement may be a better number to use when deciding between Roth and Traditional.

Now, let’s apply this to an example. Let's assume you are single and earn $70,000/year, are just barely in the 22% marginal tax bracket ($70,000 — $11,750 standard deduction = $58,250 taxable income, and pay a 5% flat-rate state tax. Your current marginal tax rate is 27% (= 22% + 5%).

In retirement, we'll further assume that you'll withdraw $50,000 annually to supplement any other income (hopefully, Social Security will still be available in some form). Let's also assume that your average (a/k/a" effective") tax rate will be 8% due to deductions.

You want to invest $1,000 for retirement and assume it will grow by 6% per year for the next 40 years. Which will fare better: putting it in a Traditional 401(k) or a Roth 401(k)?

Based on the guidelines I laid out in the previous article, and since the marginal rate today is higher than your estimated average rate in retirement, the Traditional 401(k) would be the best choice. Let's see if that holds if we run the numbers.

Option one is the Traditional 401(k). Since contributions are made pre-tax, the entire $1,000 is invested. (You’ll probably get an employer match, perhaps 100%, but that is true for both Roth and Traditional accounts.) Over 40 years, the investment grows at 6% per year compounded, so the future value (FV) is:

In retirement, you withdraw the money and pay 8.08% tax:

So, your final after-tax value in retirement is $9,455.

Option two is a Roth 401(k). Since Roth contributions are after-tax, you first pay 27% (22% marginal federal plus 5% state) in taxes, leaving you with:

Over 40 years, this investment has also grown at 6% per year, so FV is:

Since Roth withdrawals are tax-free, your after-tax value remains $7,509.

Now, we can compare both options. The tax-free Traditional 401(k) account grows to $9,455, while the after-tax account only reaches $7,509.

In this scenario, choosing the Traditional 401(k) over the Roth increased your wealth by 26%. That's a big difference!

Let's next consider another example with a very low withdrawal rate of $25,000 per year in retirement. Because of the standard deduction (assuming it doesn't change), your tax rate is 0%. But what if you have to withdraw another $25,000 for a new roof or a remodel project? If you do, $15,300 will be taxable, and the first $11,925 will be taxed at 10% and the next $3,375 will be taxed at 12% (as you have crossed into the 12% marginal bracket). Still, although your marginal rate is 12% your average tax rate is only 3.2% (= ($11,925 x .10) + ($3,375 x .12)).

A Roth 401(k) may make the most sense if you believe your average tax rate in retirement will be higher than your marginal rate today (e.g., you expect higher income or tax brackets in the future). Or, if you expect to have lots of taxable income in retirement (e.g., a pension, annuity, or Social Security), such that your Traditional 401(k) withdrawals would push you into higher tax brackets.

If you prefer tax certainty, paying taxes now guarantees tax-free withdrawals later, no matter what your income or tax brackets are in the future.

A Traditional 401(k) may make sense if you believe your average tax rate in retirement will be lower than today's marginal tax rate. If you're early in your career and expect your income to increase significantly, you may want to make Traditional 401(k) contributions to maximize your investments since they are pre-tax.

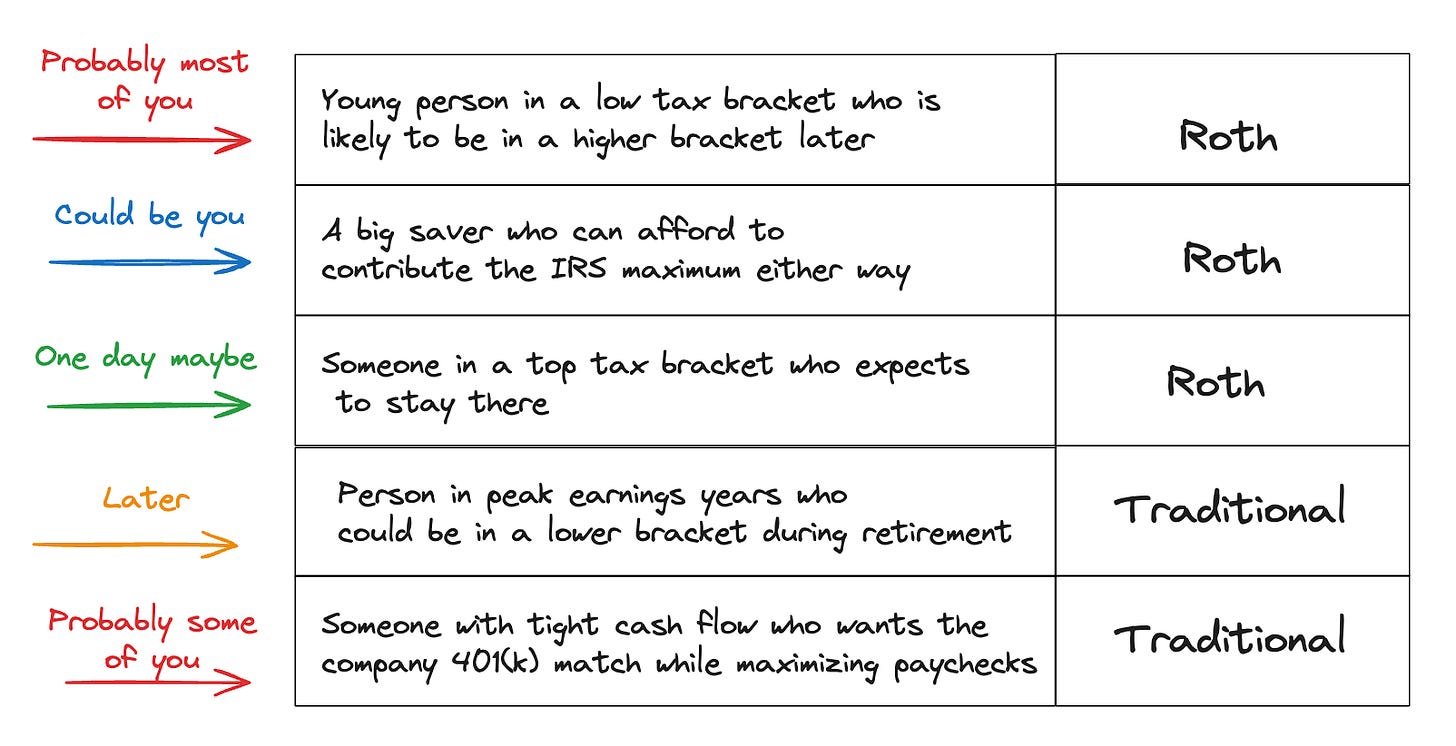

Here’s a table that describes these scenarios and others, and some guidance on which way you may want to go:

Ultimately, the right decision depends on your unique situation. However, in the earlier example, choosing a Traditional 401(k) over a Roth 401(k) increased after-tax wealth by 26%. Of course, we had to make certain assumptions about future tax brackets, which is the “fly in the ointment” for this analysis.

Up to this point, we’ve looked at this mainly as an either/or decision. But there is another option: contribute to both. Let’s say you decide to contribute to a Roth and are in the 22% marginal bracket. Depending on your taxable income, you could contribute just enough to a Traditional 401(k) or IRA to get you back to the very top of the 12% marginal bracket (which in 2025 is $96,950).

Understanding these simple tax strategies can improve your net worth over time. Make the right choice, and you'll keep more of your hard-earned money instead of paying unnecessary taxes.

Perhaps you are thinking, “This is all well and good, but what about the earlier comment you made about future tax rates?” That’s a fair question.

We can calculate our marginal and average tax rates today with 100% certainty. That gives us at least half the information we need to make an informed decision. The other information we need is our estimated average tax rate in retirement, which could be decades away and will depend on tax brackets at that time, the tax code, your income, and the size of the standard deduction, most of which are currently unknowable with a high degree of certainty.

We are all aware of the concerns about the federal deficit and debt; some believe taxes must increase significantly to address them. That's a rational view. But I still think this analysis is valid, and here's why:

Let's assume an extreme case where tax brackets in the future are double what they are today, but with everything else being the same (standard deduction, size of the brackets, etc.). So, the new brackets would be as follows:

10% => 20% for income up to $23,850

12% => 24% for incomes between $23,851 and $96,950

22% => 44% for incomes over $96,951 up to $206,700

24% => 48% for incomes over $206,701 up to $394,600

Etc.

You may think they will never get that high, and I agree with you, but let's see how this impacts our analysis. Here's how $60,000 of retirement income for a married couple filing jointly—with a standard deduction of $33,200 and spouses aged 65 or older—would be taxed under today's tax structure versus a future scenario where tax rates double.

For taxable income of $26,800, the calculation is:

In the extreme future example, the marginal tax rate is 24%, and the average tax rate goes from 4.6% to 9.1%. That may be less than you expected. But remember how it is calculated—it is the weighted average of different tax rates.

The main reason significantly higher tax rates in the future didn't have a huge impact on the average tax rate is the large 0% taxable range ($34,700) created by the standard deduction. Additionally, we maintained the standard deduction at its current level, despite occasional adjustments due to inflation. (For instance, the IRS increased it by 7% for tax year 2023 due to high inflation, and it just increased again in 2025.)

If the standard deduction is higher in the future, then the average tax rate would be lower. That said, due to inflation, $60,000 may not be enough to live on in retirement 40 years from now. If you need $160,000 instead, future tax hikes could be a big concern, and you would probably be better off with a tax-exempt account.

The ultimate hedge against inflation is to live a modest lifestyle and avoid debt as much as possible.

It's also possible that the standard deduction could shrink to generate more tax revenue for the government. However, overall, the tax code is generally favorable to middle— and upper-middle-income earners, which will likely be the case for most of us in retirement.

I’ll finish by reminding you that apart from taxes, there are some good reasons to prefer Roth accounts. Perhaps the best thing is that you have access to the money you’ve contributed at any time for any reason, since the money has already been taxed. Therefore, a Roth may be a suitable option for purposes beyond retirement.

You could use it for emergencies (principal only), a first-time home purchase (principal plus up to $10K of interest at no tax), a child’s education (principal only), and, of course, actual retirement (principal + interest without taxes or penalty). Not a bad deal!

For reflection: Ultimately, there is no current way to know the optimal decision—Roth or Traditional—decades out with absolute certainty. There are just too many unknown variables. This is true of many financial decisions we make; we have to make assumptions about future events that may or may not come to pass. How comfortable are you with uncertainty and ambiguity? Does it lead you to “analysis paralysis,” or are you okay with deciding based on your best information and letting God be God in terms of what happens years later?

Verse: “But now, O LORD, you are our Father; we are the clay, and you are our potter; we are all the work of your hand” (Isaiah 64:8, ESV).